I’m reading Kevin Kelly’s What Technology Wants which is quite good. It is a ‘book of the article’ type of book, but I like it nevertheless. Part Two and some of the chapters at the end are the best part of the book.

I’m reading Kevin Kelly’s What Technology Wants which is quite good. It is a ‘book of the article’ type of book, but I like it nevertheless. Part Two and some of the chapters at the end are the best part of the book.

Copying from the top review on Amazon sets out the basic plot.

The central thesis of the book is that technology grows and evolves in much the same way as an autonomous, living organism.

The book draws many parallels between technical progress and biology, labeling technology as “evolution accelerated.” Kelly goes further and argues that neither evolution nor technological advance result from a random drift but instead have an inherent direction that makes some outcomes virtually inevitable. Examples of this inevitability include the eye, which evolved independently at least six times in different branches of the animal kingdom, and numerous instances of technical innovations or scientific discoveries being made almost simultaneously.

And thinking about regulation, as I often do I was struck by this passage on the exponential growth of information:

The quantity of scientific knowledge, as measured by the number of scientific papers published, has been doubling approximately every 15 years since 1900. If we measure simply the number of journals published, we find that they have been multiplying exponentially since the 1700s, when science began. Everything we manufacture produces an item and information about that item. Even when we create something that is information based to start with, it will generate yet more information about its own information. The long-term trend is simple: The information about and from a process will grow faster than the process itself. Thus, information will continue to grow faster than anything else we make.

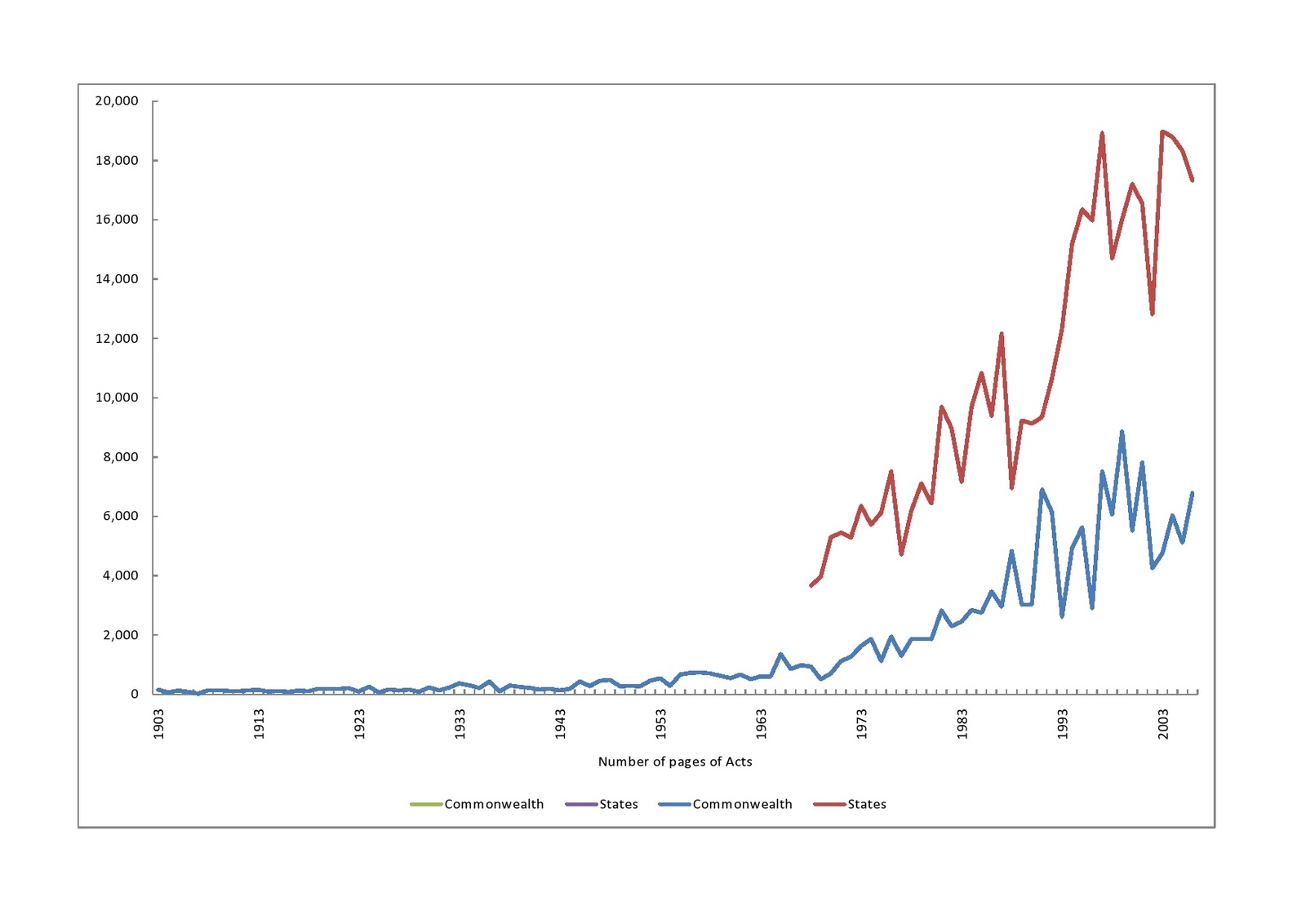

Against this it doesn’t seem so strange that the volume of regulation seems to grow something like exponentially (see diagram above and the diagram on this page). Of course that’s a scary business, because no-one can possibly comprehend all the regulation that exists – and now they can’t really do it even in some special area – like tax law. Still, it has been this way for a long, long time. ‘The law’ was impossible for any one person to know at the time of federation. For each case is part of the law, and there were thousands of pages of law to know in 1901 on any subject – comprising the hundreds or thousands of cases in the area and all the statutes and regulation.

For a long time I’ve been suggesting that those scary graphs we see of mounting regulation – measured in the pages of new legislation and regulation are not an indication of regulatory Armageddon. They’re the natural result of our lives and in particular the world of information becoming more complex. The line I’ve used in presentations is that what’s happening with regulation – which resembles an exponential growth curve – is similar to the shape of the curve measuring the size of software packages – like Microsoft Word. They just get bigger and bigger over time representing an increase in functionality.

Now it would be easy to send up what I’ve just said, and say that the mounting volume of regulation measures it’s dysfunctionality. To some extent that’s probably right – but as the world gets more complex the interactions of government with that world must become more complex. If you’re regulating finance for instance as you must even with the most laissez faire system (because you must determine tax treatment) your regulatory system must comprehend the complexity of what is evolving before it.

In some ways I’d say this is one of the flaws in Hayek. He has a strong intuition of the increasing richness and complexity of the market, but thinks the division between government and the market can be reduced to immutable principles. Of course there’s some appeal in that, but it has its limitations. Although Hayek has attracted a strong following, his vision of the rules that should be imposed upon government rule making doesn’t seem to be coming into existence anywhere. Rather government, like lots of other things is ’emergent’, and one’s political philosophy must somehow derive its vision of what should be, from some realistic understanding of what could be which is based upon a close understanding of what is and why.

And below the fold is a quote from Kelly’s book which has little to do with this post. I copied it from my Kindle to here and got the wrong quote! But it’s a good quote, so I’ll leave you with it. Over the fold.

The technium 1 is fundamentally a system that feeds off the accumulation of this explosion of information and knowledge. Similarly, living organisms are also systems that organize the biological information flowing through them. We can read the technium’s evolution as the deepening of the structure of information begun by natural evolution.

Nowhere is this increasing structure as visible as in science. Despite its own rhetoric, science is not built to increase either the “truthfulness” or the total volume of information. It is designed to increase the order and organization of knowledge we generate about the world. Science creates “tools”—techniques and methods—that manipulate information such that it can be tested, compared, recorded, recalled in an orderly fashion, and related to other knowledge.

“Truth” is really only a measure of how well specific facts can be built upon, extended, and interconnected. We casually talk about the “discovery of America” in 1492 or the “discovery of gorillas” in 1856 or the “discovery of vaccines” in 1796. Yet vaccines, gorillas, and America were not unknown before their “discovery.”

Native peoples had been living in the Americas for 10,000 years before Columbus arrived, and they had explored the continent far better than any European ever could. Certain West African tribes were intimately familiar with the gorilla and many more primate species yet to be “discovered.” Dairy farmers in Europe and cow herders in Africa had long been aware of the protective inoculative effect that related diseases offered, although they did not have a name for it.

The same argument can be made about whole libraries’ worth of knowledge—herbal wisdom, traditional practices, spiritual insights—that are “discovered” by the educated, but only after having been long known by native and folk peoples. These supposed “discoveries” seem imperialistic and condescending—and often are. Yet there is one legitimate way in which we can claim that Columbus discovered America, and the French-American explorer Paul du Chaillu discovered gorillas, and Edward Jenner discovered vaccines. They “discovered” previously locally known knowledge by adding it to the growing pool of structured global knowledge. Nowadays we would call that accumulating of structured knowledge science.

Until Du Chaillu’s adventures in Gabon any knowledge about gorillas was extremely parochial; the local tribes’ vast natural knowledge about these primates was not integrated into all that science knew about all other animals. Information about “gorillas” remained outside the structured known. In fact, until zoologists got their hands on Paul du Chaillu’s specimens, gorillas were scientifically considered to be a mythical creature similar to Bigfoot, seen only by uneducated, gullible natives.

Du Chaillu’s “discovery” was actually science’s discovery. The meager anatomical information contained in the killed animals was fitted into the vetted system of zoology. Once their existence was “known,” essential information about gorillas’ behavior and natural history could be annexed. In the same way, local farmers’ knowledge about how cowpox could inoculate against smallpox remained local knowledge and was not connected to the rest of what was known about medicine. The remedy therefore remained isolated. When Jenner “discovered” the effect, he took what was known locally and linked its effect to medical theory and all the little science knew of infection and germs. He did not so much “discover” vaccines as “link in” vaccines. Likewise America. Columbus’s encounter put America on the map of the globe, linking it to the rest of the known world.

- a term Kelly uses to mean the world of ‘technical/technological/cultural knowhow’[↩]

I’m not sure what immutable principles you have in mind here. In The Constitution of Liberty, for example, Hayek expresses specific concerns about — but does not reject — government housing subsidies, among other regulations and interventions by government, particularly in urban environments.

His name has been borrowed and abused by ideologues.

The whole thing would be a lot better if there wasn’t so much emphasis laid on the author’s apparent complete unfamiliarity with the words ‘truth’ and ‘discover’. Discover has never pretended to mean ‘reveal for the first time’, it has only ever meant ‘bring within our knowledge/awareness’.

Try putting these sentences into his framework: X discovered oil at M; Y discovered electrons; Z discovered planet P.

It almost seems like the third paragraph is a non-sequitur and the paragraphs after it are all really bland truisms.

Now that I think about the second paragraph is rather like a dictionary definition of science as well.

Now you’ve convinced me that the whole quote is really rubbish…!

Yes, a lot of information terms are subjective. To “tell a joke” implies revealing the punchline for the first time — twice is no joking matter. Each new audience receives the revelation afresh, so the same joke can be told many times, given appropriate circumstance.

Well it’s rubbish if it’s masquerading as a new insight into science. But I think the point about science being about putting things into relationship with a body of knowledge is a point which (again is not novel but) is worth making. It struck me as a worthwhile thing to say. It’s true that it’s done by reflecting on what is, when it gets down to it simply a misuse of words, but I still liked the basic point behind it.

Yes I just wish he had said it in so many words as you did.

Well he’s writing a best-seller (or attempted best-seller) from an article or two that someone said to him “Hey you should turn that into a book”.

He’s got to pad it out a little. Normally I hate that, but I quite liked this book – like I said.

Hi Nick, science is a store of knowledge and it is not surprising that it is building rapidly. I think it is a great leap though to say that regulation is similar. My own view is that transactional law has become far more innovative, particularly in banking, but whether regulation needs to be tighter in response to this innovation is a bigger question. For example, is GFC a result of loose monetary policy, a lack of oversight of asset pricing by the Fed in particular and very low savings and real mortgages compared to loan values? or insufficient reg? or both? Probably a bit of both. However my own instinct is that macro-prudential policy is far more important than the regulation of particular kinds of transactions (even if those transactions when multiplied by use are worth trillions). Obviously it is more complex than this but if we use the example of setting banks the requirement to hold more deposits this could well have prevented the asset speculation becoming so rife.

One of the reasons I hate those kinds of graphs are that most laws and regulations replace existing laws and regulations and I doubt they subtract those that become redundant. In addition, many COAG agreements mean that the states legislate but often with the same law, so even those the number of pages may spike, it could be easier to comply with the law.

Thanks Corin, but I think you misunderstand my meaning. I’m not saying that as the world becomes more complex it requires more complex regulation because there are more things to control. That’s why I said ” If you’re regulating finance for instance as you must even with the most laissez faire system (because you must determine tax treatment) your regulatory system must comprehend the complexity of what is evolving before it.”

The point is that regulation does much more than control. In the case of tax if someone invents a new kind of quasi equity, the tax system has to find a way to treat it. That leads to complexity. That’s the main point I’m making.

And if you’re regulating banks’ capital, you’ve got to figure out a treatment of some new kind of capital. I presume that the volume of accounting standards is also growing at a similar kind of clip.

I agree page numbers is a bad measure of the quality of regulation or even it’s (experienced) volume. Deregulation often leads to more pages of regulation. Thus substantial deregulation of our monopoly utilities led to the glories of price and access regulation.

So my point is that regulation is an information good and information seems to grow exponentially. So far it’s certainly the pattern of the past.

Also if the number of new laws is growing exponentially, the curve arising from subtracting some constant fraction of existing regulation as redundant would still leave one with an exponential growth curve (admittedly a somewhat flatter one).

Interesting because I’m back at ‘school’ with the new National CertIV in Building and Construction and the new chums are perplexed at the size of the BCA and relevant AS references in it. Vol1 and Vol1 with Appendix for the States. The BCA has grown rapidly in the past decade and now the Minister wants national qualifications. Sounds fine but no doubt when he asked the HIA and MBA- how’s it going the reply was – they’re not interested Minister- too much time and cost. So no doubt he threw some public bucks at them as a sweetener and a $5k course is now only $640 for the early adopters until the dough drys up. I suspect it’s- get a few on board and then make it compulsory- after all many of your peers have done it- will be the catchcry then and I can read the tealeaves. If you think we’ve got skills shortages in building now, that will certainly raise the entry bar.

What goes on on site vs those ASs and BCA is a moot point but they’re a stick to beat you with should anyone suffer anything remotely that goes bump in the night. Sustainability and energy efficiency have bloated the tomes, yet the energy consumption of a household bears no relation to a building’s energy ratings(up to 6 stars now). That’s what we need carbon taxes for apparently, to export the nasty coal in order to import all the energy saving stuff the Code calls up in order to afford the power bills that the carbon tax causes in order to… It’s a bit like that income tax act that has developed into give us a call and we’ll tell you if we like it or not. Sometimes you need to step back seriously and ask questions like- Has income tax outlived its usefulness? Has sustainability and CO2 regulation gone down the same road? Hayek is always a useful reference in answering those sorts of questions.

Not to mention that hoary old conundrum that never before in our history have so many been so educated to paper the walls of fast food joints yet so much consumer protection legislation and regualtion is necessary to protect them from the outcome.

Ok, that seems fair enough. As a lawyer by trade I agree that if I’m very skilled I will create (or replicate) an innovation for a client that perhaps gives them an advantage that policy wonks will not consider prudent for the public purse.

However I think I take an overall positive view toward limited consumer law as long as the key industries like insurance, banking and financial advice are well regulated prudentially. For example individuals may have poor financial advice but the key is whether an industry is acting in a dangerous manner.

I do agree though that tax treatment is one area which cannot but grow, see above comment about transactional innovation.

Can I also say that as a lawyer I am aware of how much accountants want to raise finance off-balance sheet and how this drives so much of the desire to regulate. It is as though the off-balance sheet desire pushes ‘innovation’ but this pushing creates unseen liabilities for companies, share holders, even public finance like PFI’s/PPP. However in Treasury departments promoted PFI’s in the 90’s and 00’s was a total dill, they should have drawn the opposite conclusion!

A lot of regulation has been driven by crony capitalism and we can recognise the familiar pattern here- http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Global_Economy/MC10Dj02.html

The classic was Westpac’s Gail Kelly spruiking hard and fast for carbon trading just as the Oz banking sector is facing an influx of savings and is struggling to find enough real investment to place it with profitably. Even their traditional Govt cossetted housing market is letting them down at present so naturally Gail is out drumming up some crony profits.

Perhaps you also realise, Corin, that off-balance-sheet financing tends to be ratings agency and prudential regulation driven, which is to say more by lawyers than ‘accountants’ as such :)

Henry Ergas has just found another area that conforms with the law of exponential growth of information work.